Stel Bailey | Environmental Health Advocate

The room buzzed with polite conversation as people settled into their seats for the League of Women Voters’ forum, Rockets Away! Risks and Rewards of Increased Rocket Launches on the Space Coast. Many of us had come expecting a raw, candid conversation about contamination, rocket fuel, sewage outflows, and the ongoing decline of the Indian River Lagoon. Instead, what unfolded felt like two parallel conversations, one grounded in lived experience, the other reaching for the stars.

The evening began with Laurilee Thompson, a Titusville native and environmental advocate whose voice carried both the weight of memory and the sting of loss. As she spoke, you could almost see the marshes and waterways of the 1950s, before dredges and pesticides reshaped them. She described Banana Creek’s transformation into a dead zone, mosquito dykes stretching southward, and rock piles trapping decaying seagrass. Her words pulled us back to a time when families lived off fishing and citrus, only to be displaced by the relentless expansion of the space industry. The room was quiet as she recounted how promises were made, some kept, many broken, and how “Engineering with Nature” was born out of decades of mistakes.

The tone shifted when Dr. Al Koller took the stage. A seasoned aerospace veteran, he radiated pride in his industry, recalling its early days and marveling at China’s achievements in space. He quoted, “We came in peace for all mankind,” before pivoting to a bold question displayed on his slides: Who owns the moon? He spoke of minerals waiting to be mined, a “lunar economy” ripe for the taking. Some in the room nodded with curiosity; others exchanged uneasy glances. For those of us who came hoping to discuss polluted waters and failing wetlands, the talk of strip-mining celestial bodies felt not just out of place, but jarring.

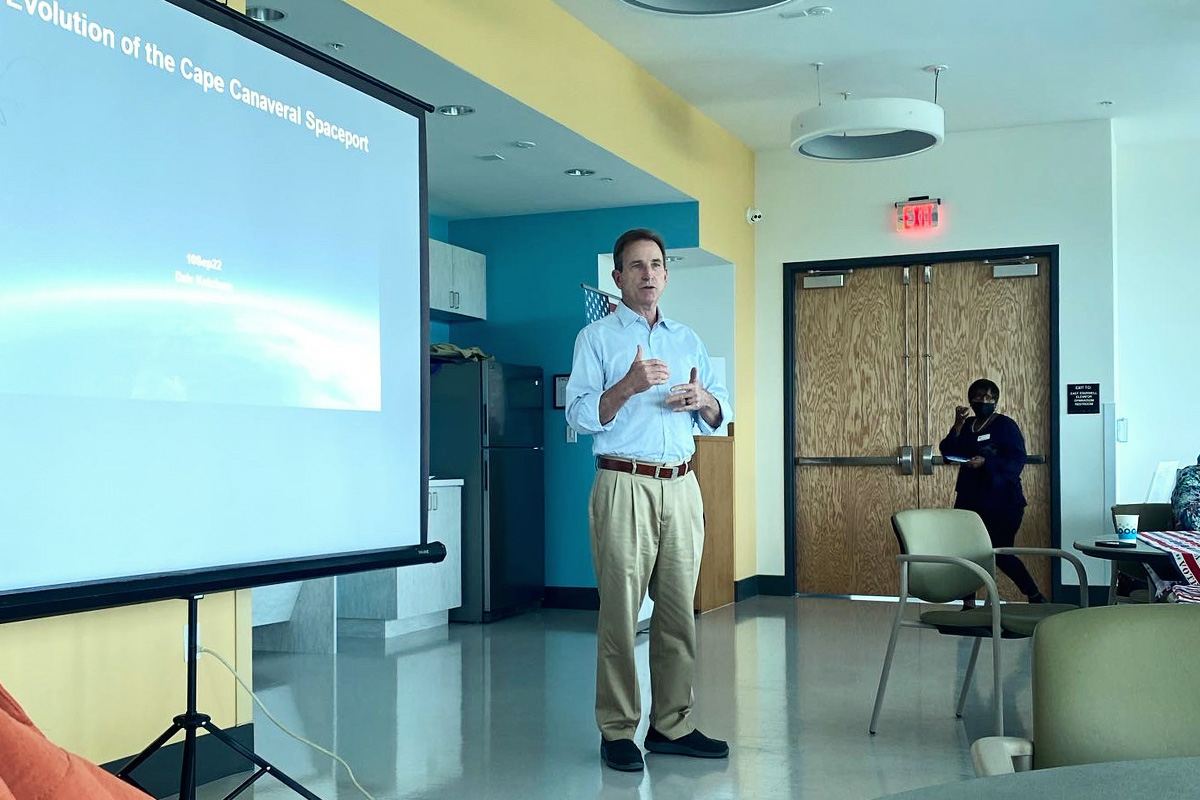

Dale Ketcham of Space Florida followed, pressed for time and racing through his remarks. He framed the National Wildlife Refuge as a gift, reminding us that without it, the Cape might be condos and shopping malls. It was an odd argument, one that asked us to be grateful for what little was preserved rather than critical of what was destroyed. He spoke of a future where families live in orbit and children are born in space pods, as though these science-fiction scenarios outweighed the sewage spills and algae blooms unfolding just outside the doors of the meeting hall.

When the floor opened for questions, frustration hung in the air. A card asking whether the industry had ever informed the public of contamination exposures was quietly skipped. Questions about sewage treatment at Kennedy Space Center were met with vague deflections. Koller admitted that rocket fuels left behind particulates, acids, and chemicals that poisoned soils and waters, but added, almost reassuringly, that “nature is powerful” and “the soil’s calcium neutralizes acidity over time.” It was the kind of answer that soothed nothing.

People leaned forward, pressing harder: What about the wetlands? The sewage plants? The Indian River Lagoon? Answers blurred into evasions. One attendee stood to say what many of us were thinking: that we cannot lure bright young minds to the Space Coast while our schools are underfunded and our waters are dying. Another warned that unchecked development at the Cape will worsen the lagoon’s decline unless strict environmental standards are enforced.

By the end of the evening, the divide was unmistakable. On one side, residents and advocates asked for honesty, responsibility, and partnership to heal a damaged ecosystem. On the other, industry representatives spoke of lunar economies, global competition, and a future where rockets launch faster, cheaper, and more often. The question projected on the screen—Who owns the moon?—was meant to inspire awe. But for many of us in the room, it only sharpened a harsher truth: before reaching for the moon, the industry must reckon with what it has already taken from the shores of Florida.